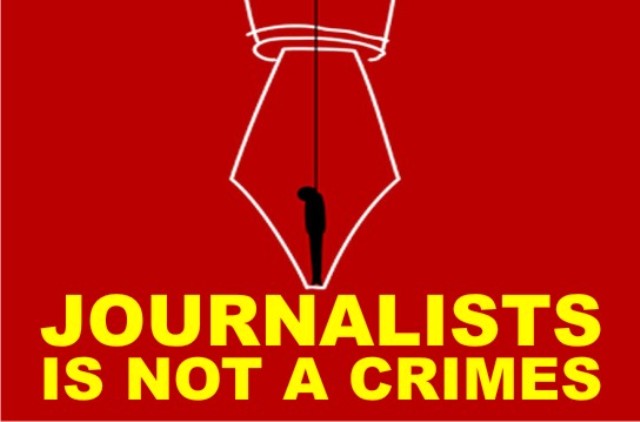

Editorial

No To Crimes Against Journalists

The observance of the United Nations International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists, once again drew global attention to the urgent need to reappraise the level of society’s commitment to security and safety of journalists and indeed the media. Reports indicate that in the past decade, over 700 journalists were killed worldwide, merely for performing their social and professional responsibility. The trend is worse, in years like 2012 and 2013 which rank as the most brutal years for journalists.

Uncomfortable with the trend, and worried by the seeming lack of commitment to the protection of journalists, the United Nations General assembly at its 68th session in Tanzania in September, 2013 adopted a resolution to set aside every November 2, to muster efforts to denounce threats to journalists and by extension, media freedom worldwide.

This year’s event drew attention to unresolved cases where violence had been used against journalists, simply exercising their freedom of expression and duty of reporting. However, this effort is yet to yield the much-expected positive result given disturbing reports that only one in 10 cases of violence against journalists has produced conviction.

The fact that new cases of violence against journalists still occur amidst failure of governments to implement their commitment to protect journalists in the performance of their duties, extra measures need to be considered to effect compliance.

A situation where media practitioners continue to report threats and intimation, from political parties, communal groups, terrorists and state security agencies and while society and those who naturally should act, look the other way, without as much as asking questions, portends an even greater danger.

More disturbing is the fact that many of the countries, Nigeria inclusive, where numerous journalist murders are still unresolved are functioning democracies. This breaks the myth that democracies are safer places for journalists because they respect freedom of speech.

Nigeria and other nations of the world must reaffirm their commitment to the safety of journalists and find solutions towards solving the unresolved murders of journalists in these countries. The killers of journalists must not be allowed to go unpunished.

The Tide insists that the Nigerian government must give account of the killers of not less than 18 journalists in the country since 1986, including the high profile murder of the Editor-In-Chief of News Watch magazine, Dele Giwa.

We agree with the declaration of UN Special Rapporteur on Extra Judicial Arbitrary Execution, Professor Christ of Heyns, that when a journalist is violently targeted and such attack is willfully left un-investigated and perpetrators not prosecuted and sanctioned, impunity is established and when such practices become the norm, impunity is entrenched.

Situations where individual journalists and media organisations are routinely subjected to surveillance, threats, harassments or physical attacks negate the exercise of their roles as a platform for democrate discourse. Such unresolved attacks that go unpunished send the signal of abuse of the rule of law.

We agree with the view that both the rule of law and the exercise of free and independent journalism can only be entrenched in an environment where willful attacks, harassments and arbitrary arrests against journalists are considered unlawful and punished.

It is against this background that we join in the call for the prioritisation of cases involving journalists as court rulings in regard to journalists resonate very far beyond the individual cases concerned. They impact on the building of human rights norms much more broadly.

Journalists on their part must continue to raise awareness and bring the issue of their safety and security on the political agenda at national, regional and international levels until a successful advocacy is achieved.

Editorial

As NDG Ends Season 2

Editorial

Beginning A New Dawn At RSNC

Editorial

Sustaining OBALGA’s Ban On Street Trading

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoAmend Constitution To Accommodate State Police, Tinubu Tells Senators

-

Politics3 days ago

Politics3 days agoSenate Urges Tinubu To Sack CAC Boss

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoDisu Takes Over As New IGP …Declares Total War On Corruption, Impunity

-

Business3 days ago

President Tinubu Extends Raw Shea Nuts Export Ban To 2027

-

Business3 days ago

Crisis Response: EU-project Delivers New Vet. Clinic To Katsina Govt.

-

Sports3 days ago

NDG: Rivers Coach Appeal To NDDC In Talent Discovery

-

Business3 days ago

President Tinubu Approves Extension Ban On Raw Shea Nut Export

-

Rivers3 days ago

Etche Clan Urges Govt On Chieftaincy Recognition